Cameras and techniques

Oct 05, 2023 by Tempe Javitz

In the 1920s Jessamine was not just a mother and business partner

with her husband, she was developing her skills with different

cameras. Camera technology advanced at a rapid pace. Not

only journalists and artists, but the ordinary person on the street

was sporting a camera and taking hundreds of photographs.

Jessamine had purchased her first Kodak in 1908, but progressed

rapidly to cameras that allowed her greater flexibility.

In 1924 she listed in her diary a new No.A. Autographic-Kodak Jr.

folding camera with an Eastman Rapid-Rectilinear lens. A rectilinear

lens yields images, such as a wall of a building, with straight lines

instead of curved ones. Her standard Kodak 3A camera, marketed

between 1903 and 1915, created a panoramic effect when she positioned

it horizontally. Cameras continued to shrink in size. Her surviving

Kodak Vest Pocket Camera, manufactured between 1912 to 1926,

I’m sure was purchased due to its handy size, 4.75 inches x .75 inches

x 2.375 inches. She would stuff it in her jacket pocket when riding.

In early August 1927 she was sporting a new panorama camera.

Jessamine’s sister, Elsa Spear Byron, purchased a #2 Eastman enlarger

for their use in 1929. She ordered it from Denver, set it up in her

kitchen in Sheridan, and began enlarging photos for both of them.

“The painted hills” of colored rocks along Rosebud Creek on the

Cheyenne Reservation, 1924.

An important question is, “How did Jessamine develop her technique as a

photographer?” Was it with the help from her mother and encouragement

from her sister? Maybe. In discussing this interesting question with my

original manuscript editor, Patty Cogen (artist and art history major),

we concluded that Jessamine’s interactions with local artists strongly

affected her resultant style and composition. In the early 1910s

Jessamine was exposed to L.A. Huffman’s photos of her father’s ranching

operation. Then her continual interaction with local artists, Bill

Gollings, Fred Miller, Hans Kleiber, Fra Dana, and Charles Belden had an

enormous effect. These artists were drawn to the Sheridan area because

of the romance surrounding cowboys and cattle ranching, local American

Indian tribes and their famous battlefields, and the stunning Bighorn

Mountains that offered such varied artistic opportunities. These

relationships heavily contributed to Jessamine’s growth as a sterling

photographer.

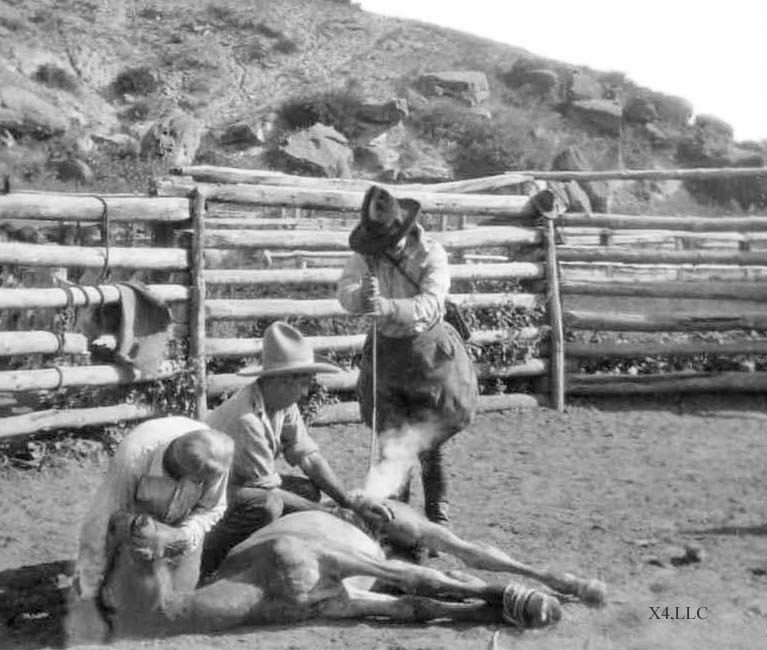

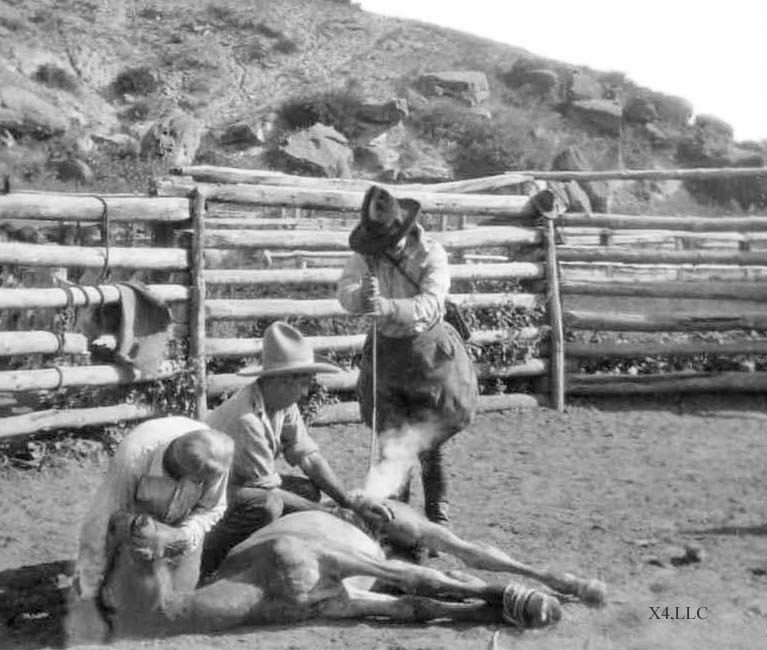

X4 Ranch branding 1920s. July 1925, Iris & Charles Rising Sun

Jessamine at first mimicked LA Huffman’s expansive cattle herd photos,

but soon narrowed her vision to single activities such as branding, breaking

a colt, or fixing a fence. Gollings’ paintings encouraged her to literally

get “close up” to her subjects to enhance the image. When taking her photos

horseback she was able to move among the cattle or cowboys by training her

horses to quickly stand still until they heard the shutter click. Hans

Kleiber’s wonderful etchings taught her a great deal about using light and

shadows to highlight her landscape images. Belden’s photos of the Bighorn

mountains and canyons were down right inspirational. These were Jessamine’s

instructors. She had no formal training, but she picked up techniques from

her artist friends and she practiced. The more photos she took, the more

she learned what worked. She rarely missed an opportunity for a camera was

always strapped to her shoulder wherever she went.

Jessamine with her camera at the ready, X4 branding 1920s.

Jessamine often used doorways, fences or trees to frame her subjects. She

used perspective in clever ways to draw the viewers eye across the photo to

converge on a distant horizon or figure.

Edelman Pass photo from 1932, Big Horn Mountains

In time Jessamine was able to convey her individual style with great ability.

Unhindered by the need to make a living from photography, Jessamine was free

to explore a wide range of genres—"from botany to battlefields.”* Jessamine

documented range life; took photos we would call photojournalism of fires,

cars, rodeos, Indian fairs and roundups; recorded changes in fashion; created

candid photos of children and grown cowboys alike; captured images of

homesteader cabins and mining sites; inspired her viewers with the peaks,

streams, and flowers of the Bighorn mountains; and captured moods and expressive

faces with her portraiture.

X4 Horses on skyline,June 1927. Torrey Johnson, Rosebud Mtn Ranch, Aug 1939

I concluded long ago, as I worked for years scanning and cataloging my

grandmother Jessamine’s marvelous photos, that here was a woman with

“an artistic eye”, who through lots of practice and many wonderful cameras

found a way to express the artiste within her. We are the lucky audience.

Cowboy Jargon:

Green Up: What the grass does in the spring.

Green Broke: A horse that has been ridden only once or twice and would

be hard to control.

Greenhorn: A person who doesn’t know their way around the West yet.

A tenderfoot or a green hand.

* A quote from Patty Cogen (my friend & editor) while discussing Jessamine

in the summer of 2018.

with her husband, she was developing her skills with different

cameras. Camera technology advanced at a rapid pace. Not

only journalists and artists, but the ordinary person on the street

was sporting a camera and taking hundreds of photographs.

Jessamine had purchased her first Kodak in 1908, but progressed

rapidly to cameras that allowed her greater flexibility.

In 1924 she listed in her diary a new No.A. Autographic-Kodak Jr.

folding camera with an Eastman Rapid-Rectilinear lens. A rectilinear

lens yields images, such as a wall of a building, with straight lines

instead of curved ones. Her standard Kodak 3A camera, marketed

between 1903 and 1915, created a panoramic effect when she positioned

it horizontally. Cameras continued to shrink in size. Her surviving

Kodak Vest Pocket Camera, manufactured between 1912 to 1926,

I’m sure was purchased due to its handy size, 4.75 inches x .75 inches

x 2.375 inches. She would stuff it in her jacket pocket when riding.

In early August 1927 she was sporting a new panorama camera.

Jessamine’s sister, Elsa Spear Byron, purchased a #2 Eastman enlarger

for their use in 1929. She ordered it from Denver, set it up in her

kitchen in Sheridan, and began enlarging photos for both of them.

“The painted hills” of colored rocks along Rosebud Creek on the

Cheyenne Reservation, 1924.

An important question is, “How did Jessamine develop her technique as a

photographer?” Was it with the help from her mother and encouragement

from her sister? Maybe. In discussing this interesting question with my

original manuscript editor, Patty Cogen (artist and art history major),

we concluded that Jessamine’s interactions with local artists strongly

affected her resultant style and composition. In the early 1910s

Jessamine was exposed to L.A. Huffman’s photos of her father’s ranching

operation. Then her continual interaction with local artists, Bill

Gollings, Fred Miller, Hans Kleiber, Fra Dana, and Charles Belden had an

enormous effect. These artists were drawn to the Sheridan area because

of the romance surrounding cowboys and cattle ranching, local American

Indian tribes and their famous battlefields, and the stunning Bighorn

Mountains that offered such varied artistic opportunities. These

relationships heavily contributed to Jessamine’s growth as a sterling

photographer.

X4 Ranch branding 1920s. July 1925, Iris & Charles Rising Sun

Jessamine at first mimicked LA Huffman’s expansive cattle herd photos,

but soon narrowed her vision to single activities such as branding, breaking

a colt, or fixing a fence. Gollings’ paintings encouraged her to literally

get “close up” to her subjects to enhance the image. When taking her photos

horseback she was able to move among the cattle or cowboys by training her

horses to quickly stand still until they heard the shutter click. Hans

Kleiber’s wonderful etchings taught her a great deal about using light and

shadows to highlight her landscape images. Belden’s photos of the Bighorn

mountains and canyons were down right inspirational. These were Jessamine’s

instructors. She had no formal training, but she picked up techniques from

her artist friends and she practiced. The more photos she took, the more

she learned what worked. She rarely missed an opportunity for a camera was

always strapped to her shoulder wherever she went.

Jessamine with her camera at the ready, X4 branding 1920s.

Jessamine often used doorways, fences or trees to frame her subjects. She

used perspective in clever ways to draw the viewers eye across the photo to

converge on a distant horizon or figure.

Edelman Pass photo from 1932, Big Horn Mountains

In time Jessamine was able to convey her individual style with great ability.

Unhindered by the need to make a living from photography, Jessamine was free

to explore a wide range of genres—"from botany to battlefields.”* Jessamine

documented range life; took photos we would call photojournalism of fires,

cars, rodeos, Indian fairs and roundups; recorded changes in fashion; created

candid photos of children and grown cowboys alike; captured images of

homesteader cabins and mining sites; inspired her viewers with the peaks,

streams, and flowers of the Bighorn mountains; and captured moods and expressive

faces with her portraiture.

X4 Horses on skyline,June 1927. Torrey Johnson, Rosebud Mtn Ranch, Aug 1939

I concluded long ago, as I worked for years scanning and cataloging my

grandmother Jessamine’s marvelous photos, that here was a woman with

“an artistic eye”, who through lots of practice and many wonderful cameras

found a way to express the artiste within her. We are the lucky audience.

Cowboy Jargon:

Green Up: What the grass does in the spring.

Green Broke: A horse that has been ridden only once or twice and would

be hard to control.

Greenhorn: A person who doesn’t know their way around the West yet.

A tenderfoot or a green hand.

* A quote from Patty Cogen (my friend & editor) while discussing Jessamine

in the summer of 2018.